Water rushes below the Mill of Amaiur in Spain’s Baztan Valley, but it’s the rain-like patter of corn being milled into puffs of flour that has captured my group’s attention—that, and the promise of talos, a Basque specialty similar to Mesoamerica’s corn tortilla.

Here in the rolling Spanish Pyrenees, just a stone’s throw from France, they stuff them with farm-fresh cheese, chorizo, bacon and chocolate. Felipe Oyarzábal, who owns and operates the mill and overhead B&B, says the village’s relaxed pace is quiet reprieve for some during Pamplona’s hectic San Fermin festival. Sitting on a picnic bench beside a gushing waterfall, watching oozing cheese talos almost magically disappear from the table (Baztan cider in hand), I’d venture to say his tastings also have something to do with it.

As part of the Kingdom of Navarra, Amaiur-Maya is a peaceful stretch of land where shepherds still watch over their flocks and one could set a watch to a farmer’s siesta. Like most bucolic settings, however, the hills also hold, and sometimes bury, the past. It was here that the Spanish brought the Kingdom of Navarra to an end after a 900-year rule. And, it was here in Baztan that thirsty pilgrims trekking the Camino de Santiago (Way of St. James) helped to keep Navarra’s viticulture alive through the centuries—over 200 wineries now dot a region around 100 miles wide. Today, the valley adds a table full of American journalists to the mix, beckoning us to eat and drink like kings.

True-to-culture F&B experiences like these hallmarked our 6-day jaunt through Navarra, sponsored by the Navarre Tourism Board, discovering in the end what Francisco Glaria, director of Novotur Guides, told us to expect from the beginning: “Spanish magic—making life comfortable and beautiful—is Basque heritage. Spain is much more than paella.”

Moments Not Meals

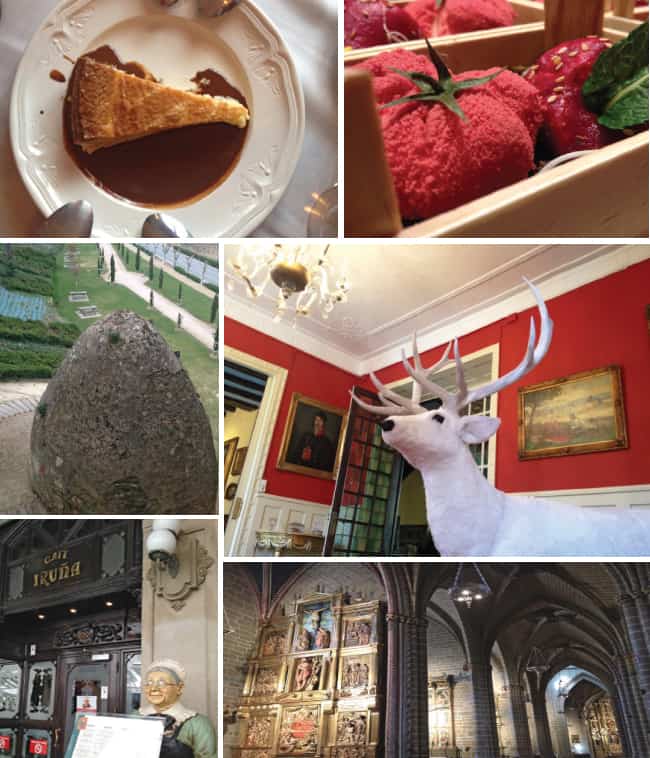

Navarra’s culinary scene revolves around the seasons. The result is a hyperlocal foodie culture keen to create moments instead of meals. Geographical diversity almost ensures that every region specialize in something—according to Glaria, “now is the moment for white asparagus” in the quaint town of Olite, the seat of the Royal Kingdom in medieval times. Farm-fresh vegetables and wines are the pièce de résistance here, considered the culinary heartbeat of Navarra. Local businesses, like the medieval Parador de Olite hotel, thrive on the farming cooperatives that deliver fresh, organic produce, a.k.a., a table of perfection. The palace, once elaborately donned with fairy-like gardens, whimsical towers and even a zoo, can be rented for cocktail receptions—a light Homenage rosé or another of 100 wine varieties surely on the menu. Be sure to bring your group by the pozo del hielo (ice well), near the Ochavada tower for a gander at the medieval structure of Jurassic proportions that once stored the castle’s food supplies.

“Spanish magic—making life comfortable and beautiful—is Basque heritage. Spain is much more than paella.”

Though not necessarily in Olite, legend has it that churros were invented by nomadic Spanish shepherds traveling through these parts—not too far from here in Pamplona, they’re cooked over an ax-cut beech wood fire, rolled in wheat from the desert Bardenas and fried in olive oil. What you do with them after this is your own business, but locals dust with sugar or drizzle in chocolate.

Nowhere is Navarra’s seasonally-charged fare more evident than Semana del Pincho, or Navarra Pincho Week. In Pamplona and nearby towns, it’s the largest annual competitive culinary festival where hors d’oeuvres become delectable masterpieces, almost too pretty to eat—but with a price of two pinchos for around $4.50 ($6.50 with a glass of wine) across the city, you’ll certainly find a way. Glaria says in the north of Spain, Michelin stars have to fight hard against pincho bars, which he considers to be more like a psychiatrist’s office, or “a place where you share yourself.”

“The pincho experience, [chiquiteo], goes beyond food—it’s about friendship, getting together and sharing a conversation. In today’s life we tend to forget to talk with people, we Facebook everything but we don’t talk, so I think pincho bars are more about going back to basics. It is you, a friend, wine and good food.”

Even the most elaborate pinchos maintain a back to basics edge to some degree. Take “Waves Crashing Against Rocks,” named for the crests of the Navarrase Pyrenees that stretch toward the sea. Served on a slab of gray rock, the two-part pincho begins with a garlic and olive oil-filled razor clam. “She’ll open the taste buds with fat,” our server says of the clam, “so you’ll have an explosion of flavors.” The second step is one big bite filled with baby squid, pig noodles, shrimp cake and veil tendon. Flavorful seems to be an understatement, and as far as ambience goes, it’s hard to get more back to basics than La Capilla in Pamplona Catedral Hotel, a chapel-turned-restaurant within a convent-turned-hotel. At Abaco restaurant in Huarte’s Museum of Contemporary Art, we’re introduced to “street food” pinchos and in one bite you can certainly see why pincho bars are giving Michelin-starred restaurants a run for their money. Brothers Jesus and Luis Inigo took home the gold for their soft and crunchy bread and fish concoction inspired by the East. In all, close to 80 businesses participated in Pincho Week, a steady climb in participation from previous years.

“The pincho experience, [chiquiteo], goes beyond food—it’s about friendship, getting together and sharing a conversation. In today’s life we tend to forget to talk with people, we Facebook everything but we don’t talk, so I think pincho bars are more about going back to basics. It is you, a friend, wine and good food.”

Torrents of Spring

It’s close 1 a.m. and Pamplona’s iconic Estafeta Street seems to be just getting started. If Hemingway were still alive, there’s a chance he’d be draped over the railing a couple stories up from where we stand for the running of the bulls a few months from now. The 19th century 5-star Gran Hotel La Perla rents out plush pink room 201 for a pretty penny during the running of the bulls. Rooms also overlook the Plaza del Castillo, with its wide open courtyard and twisty trees—no less part of the Hemingway route with views of Café Iruna, a notable spot of inspiration for the author. Elsewhere in Pamplona, culturally-infused venues seem made to deliver high-impact culinary experiences. Aside from marking the spot where kings were once crowned and Parliaments convened, events are regularly held in the 14th century Cathedral of Pamplona, a womb of gold and rich polychrome that is surrounded by the most historic and artistic relics in the city, including the oldest remaining image of the Virgin Mary in Navarra.

“We also have a bull farm ranch,” Glaria adds. “They do capeas (a kind of bull fight that you can participate in).”

An obvious highlight to any cultural food & beverage program is the exhibition space at the roughly 700,000-sf Baluarte Congress Centre and Auditorium of Navarra, anchored by the remains of five 16th century bastions of the Citadel of Pamplona. Both the exterior wall and the interior buttresses of the bastion grant a strong sense of place, while at the same time serving as an empty canvas for your meeting and event needs. Another unique space cradles attendees in sweeping views of the city. The open-air terrace, which overlooks the Citadel, a 16th-century fortress-turned-public park, is a hot spot for cocktail receptions and taking in the fireworks during San Fermin.